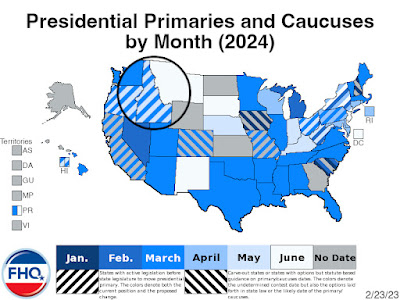

The Connecticut Joint Committee on Governmental Administration and Elections convened on Monday, March 20 to conduct initial public hearings for a number of bills,

HB 6908 among them. That legislation would shift up the date of the presidential primary in the Nutmeg state to

the first Tuesday in April starting in the 2024.

No votes were taken on the measure, but the testimony given offered insight into the motivation behind the bill. Testifying together, the chairs of the two major state parties supported the move and indicated that it was the potential for greater influence in the presidential nomination process that prompted them to cooperatively help craft the legislation. Nancy DiNardo, the Connecticut Democratic Party chair noted that the change would give the state a "stronger voice in choosing a presidential candidate" and was furthermore "proud to say this legislation is bipartisan."

Connecticut Republican Party Chair Benjamin Proto said that an earlier primary would give Connecticut "more influence within the presidential nominating system as well as to provide voters more engagement within their party and with candidates."

Nowhere in either the oral or

written testimony did either mention the current primary date's conflict with Passover in 2024. Instead, the parties were motivated by potential influence rather than that conflict in moving the primary. However, the move would shift the Connecticut presidential primary out of a conflict with the tail end of Passover.

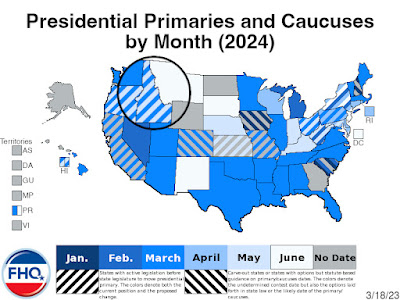

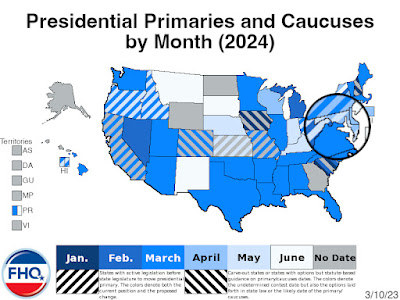

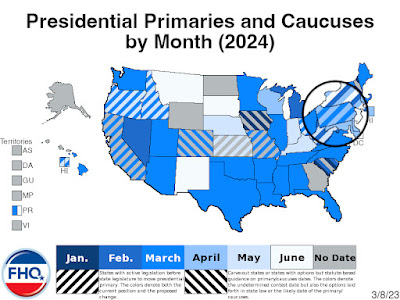

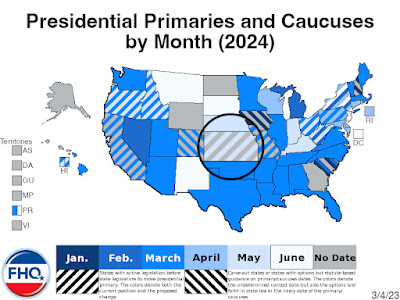

None of this is groundbreaking news. State legislators consider presidential primary bills every year (but particularly in the year before a presidential election) to move contests around. And frequently among the top stated reasons for the legislation being introduced is the quest for more influence in and resources from the presidential nomination process. Often it is a fool's errand because the states that draw that kind of influence are the (protected) earliest states and the next wave is a cluster of contests within which states -- especially smaller ones like Connecticut -- often get lost.

However, what was noteworthy about the testimony of DiNardo specifically was that she noted that shifting the Connecticut presidential primary to early April would align the election with the primary in

New York. Now, either that was a mistake or there have been conversations among Democratic state parties about coordinating a landing spot for the two neighboring states' primaries.

There are efforts to move the New York primary. However, none of them target an

early April date. Plus, the standard operating procedure in New York for setting the primary date is for that work to be done in the late spring (in the year before a presidential election) in consultation with the state parties in the Empire state.

Nonetheless, this potential cooperation makes sense. But for Covid, the Connecticut and New York primaries would have coincided in

two of the last three cycles. And that sort of subregional cluster of contests would potentially be a bigger draw to candidates than if either state were to go it alone. On the Republican side, an early April position would also allow both

Connecticut and New York Republicans to retain their current variations of the

winner-take-most rules.

Of course, both efforts have to make it through the legislative process first. And the Connecticut push has only just begun. In New York, they are not even that far along.

--

See more on our political/electoral consulting venture at FHQ Strategies.